Chapter 10

A Tale of

Two Summers

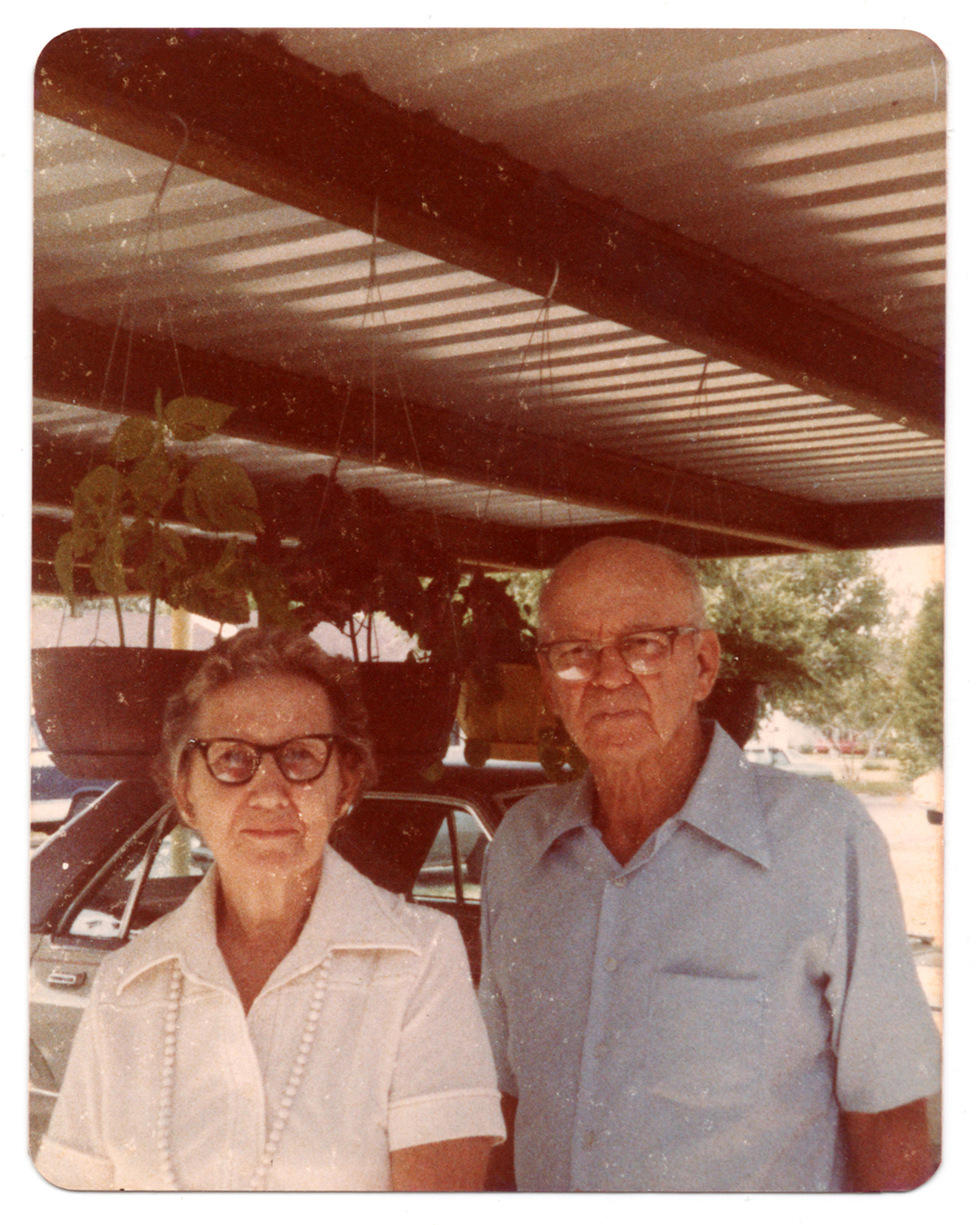

Photo: Oyster Lake, 1975.

Written by Michael Blankenburg

Published June 10, 2013

Until I chose gainful employment at Baskin-Robbins at age sixteen, summers meant a four-hour Trailways bus ride to a small town outside of Houston to see my father for one miserable week. Mom spent several days before our departure coaching us to behave, as Nanda loved to say, like young men, not little pigs. The last thing she wanted is for us to make a bad impression, suggesting to our father that her single-parenting was in any way lacking.

According to Dell Rose, it was Wendel’s emotional impotence that had crushed the marriage. She wanted romance, adventure, art and music. She wanted love notes and surprises and to be the center of attention. Wendel was far too pragmatic, indifferent to whimsy. So Dell Rose set out to occupy her gregarious nature and creative talents. She studied cookbooks on how to make the perfect souffle. She set the table and served dinner by six. She even hand-dyed the lifeless beige carpet a deep emerald green.

“You changed the carpet,” he said.

“Yes, you like it?”

“It’s green.”

Wendel wasn’t much for words. After several Miller Lites, Mom would retell through slurred speech the story of the straw that broke the marriage’s back:

“Wendel, do you love me?”

“What? What are you talking about?”

“Do you love me? Really, truly love me?”

“Well, I married you, didn’t I?”

Silence.

“Isn’t that enough?”

It wasn’t. Her leaving stung our father who married his second wife not long after. She already had three girls from her previous marriage. Instant new family. Communications with us were the perfunctory birthday and Christmas cards and the rare awkward phone call. Any face-to-face contact was limited to these one-week summer visits with a practical stranger.

Just off the bus my father would give me a firm handshake, pat my belly, and say something like Lookin’ a little rolly-polly there, Mike! followed by a wink and chew on his cigarillo. I never thought it funny. Always proud of his trim and fit self, he felt an obligation to point out those who weren’t. Tall and skinny, Danny had no worries there. From the bus station we headed directly for the house he built with his own two hands and helped trim trees on his five-acre lot or dig potatoes in his enormous garden. Some years we’d get the luxury of staying in a rented beach house on Galveston Island, where the wide expanse of shore and sea seemed to loosen his militaristic grip on petty rules and decorum. But on his own turf, under the watchful eye of my stepmother, Pat, it was no vacation.

My brother and I were once greeted by a pair of shears just minutes upon arrival when Pat declared, We’re going to make sure you two look like young men, not little girls. We sported the style of the day circa ’76, our hair worn over the ears and just beyond the collar. This would not do. Sitting on a barstool outside and listening to the menacing buzz of the clippers, I watched through teary eyes as my Shaun Cassidy locks fell soundlessly to the deck, imagining the countless ways I’d finally tell Pat how much I hated her.

Insult to injury followed at dinner where, beholden to some obsessive natural law of eating, my father only served food from his garden or game that he had killed. Instead of the boxed Hamburger Helper, canned green beans and frozen pizzas I was used to, it was squash, spinach, cabbage or collard greens the mere smell of which made me gag. Thank God for the slice of homemade bread. If meat was served, it was never anything recognizable. It was something awful like tripe or mountain oysters. Where was the rest of this animal? And why did we have to eat its guts and testicles? Sometimes I’d sneak a strange ball of meat or two into my napkin and put it in my pocket for later flushing. Fighting back his own gag reflex, Danny would pinch me under the table and whisper just eat it… don’t be such a baby. But there was good reason for tears. My barely overweight step sister had to fight back her own. You don’t need another slice of bread, Jen. You’re already fat. And you wonder why, my father taunted. Not cleaning your plate meant Saran Wrapped leftovers served to you again at breakfast while everyone else enjoyed the only normal meal of the day—pancakes, bacon and eggs. Pat shook her head and could barely restrain a sardonic smile at the horrible job my mother had done raising us. No matter how quietly I tried to eat, it was, in her over-enunciated delivery, Kah-Loze yo-wer Ma-ow-thuh and to my brother, who hung his head over his plate, Danny. Bring yo-wer Fo-werk to yo-wer Ma-ow-thuh. Not yo-wer Ma-ow-thuh to yo-wer Fo-werk. Then Pat would raise her head as if sniffing something afoul, pronounced underbite at attention, and hold an icy glare.

It was Pat who brought my father back to church (hers), some nondenominational branch with a guttural-sounding name. And I thought the dinner rules were harsh. Services were held every weeknight and twice on Sundays. Saturday was the only day off. For services there was what my step sisters called Big Church and Little Church. You had to be fourteen to attend Big Church where hundreds sat in an auditorium and took notes as the preacher furiously scrawled Latin and Greek terms like agápē in large jagged letters on the overhead projector. This was serious stuff. A schoolboy at heart, I liked the idea of bringing a spiral notebook and an assortment of colored pens, looking all diligent. I practically shouted Hallelujahs when I finally graduated Little Church, the one for babies, and headed for adulthood in Big Church. But this was scary church. Pictures of U.S. presidents and military leaders lined the halls. American flags hung at every doorway. Two R.O.T.C. cadets stood sentry at each entrance, bouncers if the crowd got out of hand. It felt very Third Reich. During one service, two teenaged girls were escorted outside for whispering during the sermon. Evil bitches. As a preventative for such restless, undisciplined behavior, each service began with a prayer that included asking God to still our bodies and open our minds. I just prayed for the long week and even longer service to finally end, knowing that my idea of heaven wasn’t the kind they described here in Big Church. My idea of heaven was waiting for me around a curve of Blue Creek Road.

All the spirituality I could ever want I found at my grandparents’ house in El Campo on Blue Creek Road—the smell of baked bread and homemade molasses cookies, a plate of fresh sliced tomatoes, a rambling yard full of lazy tomcats, and the resonant low hum of the box fan in the garage. Grandpa hovered over his workbench fumbling with the ultimate fishing lure while I hammered various sized nails into a piece of two-by-four. I was supremely happy.

My father’s parents—stable, active, (prescription) drug and drama free—were the antithesis of my mother’s. Unlike my mother’s parents, where alliances were formed and dissolved in the blink of a suspicious eye, these grandparents never strayed from their supporting roles, never uttered a harsh word or sought motivation through guilt. They were just Grandma and Grandpa. Never a more beautiful simplicity. Or one more needed.

This Gilded Age lasted one glorious month. The long days seemed inexhaustible, time slowing to a crawl. But I was never bored. I had grandpa’s guided tours through a leafy vegetable garden, swimming in the frigid rice canals, endless games of Crazy Eights with grandma, and sweet cantaloupe savored while perched on the silver propane tank next to the gravel drive. Tuesdays we ventured into town. With grandma buoyed by a phone book and pillow at the wheel of her steely blue Impala, we headed for groceries at Stanley’s Super, her weekly B-12 shot at Dr. Presley’s, and finally, to Perry’s Five-and-Dime where Danny and I had the luxury of choosing one toy each.

Sunday morning was church, but nothing like the tyranny of Big Church. The Lutheran church my grandparents attended, a white stone building nestled in a grove of pecan trees, was small and intimate. The recitation of psalms and choral responses—the Lord, hear our prayers and Peace be with yous—never seemed threatening. I was calmed and comforted by these rituals. Grandpa took his own comfort, falling asleep and startling himself awake with a snort or a gentle nudge from grandma. Taking in all of the stained glass windows rich in their greens, reds, and blues, I was particularly spellbound by the large oval panel behind the dais where a long-haired handsome Jesus knelt in an emerald green pasture, stroking the wool of a pure white lamb. (I imagined my stepmother, Pat, gladly taking her clippers to both lamb and son of God.) After church grandpa greeted anybody and everybody, engaging in extemporaneous histories of farming and fishing, who’d done what to their land and the hyperbolic stories of the latest big catch. Offering more than a simple nudge this time, grandma locked her arm around his and towed him to the car.

The main event of our stay was the three-day fishing trip at Oyster Lake in Matagorda County. We carefully studied the Sports Afield calendar for June and July, circling those days where the fish icon was not merely an outline or half-colored but a solid red, denoting the “best” fishing days of the month. Please, please, please, we gotta go! We just gotta! Grandma stocked the Igloo with homemade pickles, bread, fig preserves and plenty of cornmeal for the expected haul. Grandpa packed tackle boxes filled to the brim with hooks and sinkers, spinners and spoons, purple rubber worms and stainless steel buck knives. Danny and I spent half a day meticulously loading the van with tents, lanterns, aluminum lawn chairs, bait buckets, flashlights, fish nets, and the granddaddy seine.

It felt like a whole day’s sojourn to finally reach our destination when, in actuality, the drive was just over an hour. But the excitement of setting up camp and the smell of salt air revived us. Before we knew it fresh bait was caught, trot-lines set, and four poles stood in succession. I preferred to fish with a cork so that I had visible warning of the impending catch. Flounders were my favorite, infamous for their slow, sideways tug, the faded orange buoy gradually succumbing to the murky waters of the bay. Though not a real outdoorsman like my brother—who cast the perfect net, never flinched at the squirmy bait and flicked his rod with commanding skill—I fished with the patience and tenacity of an Old-Timer. I sat, stood or squatted all day, my sunbaked skin turning a bright pink, in wait for that moment when my pole bent into a suggestive arc and some thing, some other moved in opposition. There was no telling what laid beneath the water’s surface. Indeed, we sometimes caught strange creatures like hammerhead shark, stingray, snake eels or puffer fish. We even caught a pair of pants and a chair.

At dusk we cleaned the caught fish for grandma to fry up for dinner on the Coleman stove. Grandpa, in his white Gilligan’s hat bejeweled with fishing lures, waded into the bay with a cast net over his shoulder. Afterward, Danny and I set our rods into holding posts and prepared to stay up all night in our tent, drinking black coffee from a thermos while listening to Hall & Oates on a small hand-held radio.

Oh, won’t you smile awhile for me, Sara Oooh, oooh, oooh, oooh Oh, smile awhile, won’t you laugh, Sara I mean Smile, thank you for making me Oooh, oooh, oooh, oooh

“Wait. Shhh,” Danny turned down the radio.

“I thought I heard it too,” I said.

“Better check.”

He unzipped the door flap to our tent and slipped out into the moonlit night. I heard the soft swish of his footsteps on sand. We’d been waiting vigilantly for the magical click-click-click of the reel that sometimes spun into a high-pitched Zzzzzzeeeeeeeeeeeeee!

“Nothing yet. Just the wind,” he said, popping his head back inside.

“There will be. I can feel it,” I said.

“Yeah, we’ll get ‘em by mornin’.”

“Sleepy?” I asked, swallowing a yawn.

“Nah, you?”

“Me either.”

The wind picked up again, rustling the canvas walls of our tent as we huddled close to the kerosene lantern and talked through the night.