Chapter 3

All That

Glitters

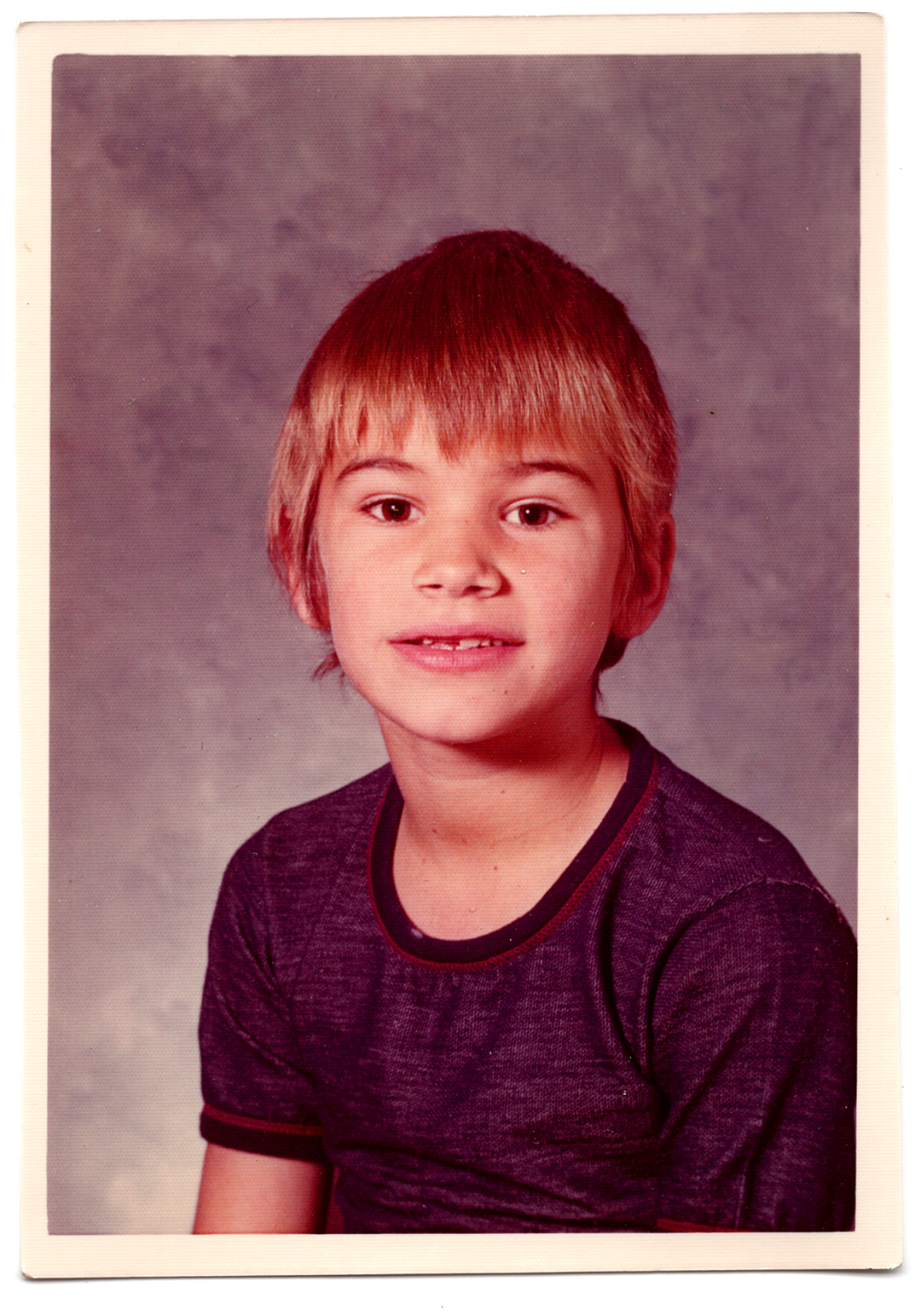

Photo: Mom holding “Drifty” our parakeet with Danny and Me. Kilgore Arms, 1974.

Written by Michael Blankenburg

Published March 04, 2013

By the time I entered first grade mother was twice married, twice divorced. We’d made our way from small town South Texas to small town East Texas with year-long stints in a Houston suburb and a god-forsaken, red clay barren strip of land outside Shelbyville. We’d landed in “The World’s Richest Acre,” a town once known for its prolific oil production but more recently lauded for its precision dance team, the Kilgore Rangerettes. Papaw had been transferred there years earlier for work with Texaco Pipeline. After a brief, claustrophobic stay at Nan and Pap’s, we moved into our very own apartment at the corner of North Street and Highway 259. Within mere blocks were the city park with its soaring red rocket slide, the Ty-D-Bol blue waters of the city pool, and the glinting limestone of the sprawling public library, not to mention other childhood essentials such as Gibson’s Department Store and Dairy Queen. Clearly we had found ourselves in the geographic and cultural center of town, our little home on an asphalt hill.

Throughout my seven-year tenure our apartment complex bore names such as The Arms, The Oaks, Tanglewood and, finally, the even more appealing Tanglewood II. I remember getting off the school bus to painters blanketing the previous signage with their rollers and my wonder at yet another new identity. With its nondescript rectangular shape, our complex resembled a rather pedestrian roadside motel more than an apartment building. But it felt like we were urban dwellers, almost city-folk, atypical of the majority of townspeople who lived in tree-lined, wood-fenced neighborhoods. Besides, I thought it pretty cool that we had wooly gold shag carpeting and were located on the second floor with a view of Exxon’s street-lit rotating sign.

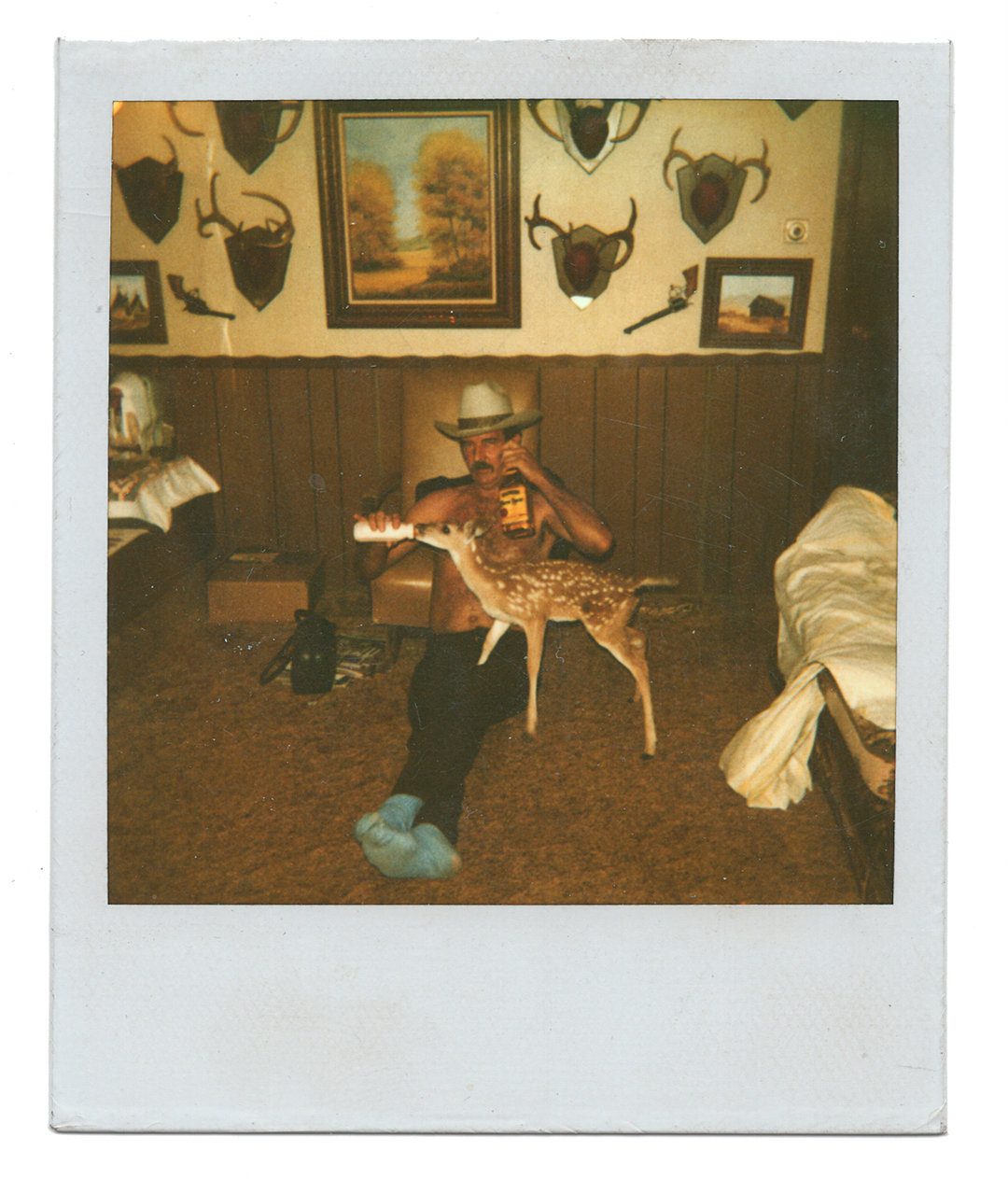

In order to make ends meet, mom worked two jobs—one as a payroll assistant across the street at Gibson’s and the other waitressing at Don’s Supper Club—which left her tired and testy. So there was the ever-present dance around her unpredictable disposition. She’d have the occasional male guest and one in particular, a hairy-chested cowboy we called Marlboro Man, became a mainstay in her life (off and on) for the next thirty years. And as various other men came and went, Danny and I would lay awake at night in our shared double bed debating who she’d choose for her next husband, our next dad. We rooted for the quiet cowboy, but he wasn’t the marrying kind.

Other than ordering take-out from Sonic or Dairy Queen, TV was the big evening event. Sunday nights began with the ominous, fear-striking-in-the-hearts-of-all ticking of the 60-Minutes stopwatch which meant the carefree weekend, the long days at the public pool, the fort making (both inside and outside the house), and the “can-I-spend-the-night” calls were over. But we’d settle in for Kraft Macaroni & Cheese and mom’s Hamburger Helper, a beloved Sunday night special. Apartment living sans dining room allowed for casual eating rituals which involved flimsy faux wood TV trays or more often our being splayed on the floor with towels under our plates, glued to the console watching The Sonny & Cher Show and Little House on the Prairie.

Whatever the realities of our current economic standing, I spent countless Saturdays devising totally implausible get-rich-quick schemes. My sidekick, Michael D., was a year younger and even more unsure of himself than I. He lived directly behind our complex in a run-down two-story house under a slew of perennial renovations that never seemed to progress. We’d met at the bus stop at the bottom of the hill where our properties ended. Because his family had just moved in, he kept asking me if he was taking the right bus. I remember the stubborn cowlick he’d try to tame with spit and a few pats of his fingers, the dirty nails in need of a trim. I remember that oversized hunter green parka he wore with the fur-fringed hood. He would become my constant comrade and companion for all boyhood exploits over the next several years. And perhaps none more important than our forays into creative commerce.

In lieu of the typical lemonade stand, it was homemade air-fresheners in used plastic butter tubs with ripe honeysuckles stolen from old Mrs. Queener’s tilting, almost horizontal chain-link fence. These feats of daring were not to be taken lightly. For Mrs. Queener was a cross between the Old Lady with Thirteen Cats and To Kill a Mockingbird’s Mrs. Dubose. She taught piano lessons on Tuesday and Thursday afternoons, her open windows with sheer ivory curtains breathing out fumbling arpeggios which escaped across her pristine lawn and up through the crepe myrtles. This idyll was often shattered when DO NOT WALK ON THE GRASS became let’s see what happens when ole Mrs. Queener sees us walking on her grass. Her shrieks of I’ll call the po-leece! And don’t think I won’t do it! I’ll call yer mother, too! were fearsome threats that never materialized. But they could have.

Michael D. and I would toe the corner of her lawn and grin with anticipation. Then one would shove the other as the actual follow-through jangled our nerves. I don’t know how, but Mrs. Queener could see us coming even before we thought it. She was a ghostly apparition inside the house, a disembodied voice with a shock of white hair. But one toe on one blade of her grass and she’d spring to life, gaunt-faced and peer out her window screeching, I TOLD YOU BOYS!!… but we’d already high-tailed it for home.

Much to our chagrin, the air-fresheners were an instant hit but the delicate and ephemeral nature of our product and the risks involved in procurement made us consider other alternatives. So we moved on to water balloons of various sizes and colors for older neighborhood boys engaging in summertime war games (we enlisted and eventually lost our remaining inventory); then, raspberry and orange Jello packets mixed together, emptied into cupcake doilies with used Popsicle sticks, our own version of Lik-A-Stik. And not to mention our unbelievable luck in striking oil in our very own backyards.

Actually it was none other than the black, grimy deposits found alongside the water drains in the local city park. We’d been boat-racing sticks in the miniature river-rafting waters when we first spied the dark pooling fluid. Dixie cups in hand, we scooped the “oil” and headed off to the Dairy Queen, the ultimate reward for a hard day’s work. We decided against going inside and walked up to the drive-thru window—an afternoon of gutter-diving had left us pretty grungy and we knew well the NO SHIRT NO SHOES NO SERVICE rule.

The glass window slid open and a bored young girl, probably a teenager though she might as well be thirty to us, grinned skeptically and asked for our order. With arms outstretched, elbows locked and cups clasped in our grubby little hands, came the announcement (in unison): WE STRUCK AWL! Without skipping a beat, our girl raised a lone eyebrow and replied, “Oh ya did now and how’dja do that?” I made up a long and unconvincing story about spottin’ a bubblin’ crude at the back of my property and she stopped me before I could finish. “Wait here a sec,” she turned, disappearing behind the shelf of clothespinned orders awaiting the line cook. In the moments before her return Michael D. and I stared at one another. Could this be? Did it work? Not knowing if the wonder was at our powers of creative invention or in the possibility that maybe, just maybe we did find something in the drains of city park. The girl returned beaming, “Man’ger says it’s worth two dipped cones!” She made our treats and delivered them with a wink. Stunned, we took our perfectly shaped chocolate domes with their signature curlicues resembling the minarets of Moscow. Now what?

“We can git more,” I assured her.

“Yeah, we can git more,” Michael D. echoed.

But we’d overstayed our welcome, gotten too greedy. With her arms akimbo and an exasperated sigh, we knew it was time to move on.

For our second act we rounded up abandoned bricks in the alley behind my apartment complex. We’d used these bricks before as impromptu cars and trucks and, as boys are want to do, for the celebratory act of destruction. I’d run to the second floor balcony with a brick in hand and hang perilously over the wood railing ignoring the sting of a few errant nails. Eyeing my target with the precision of a marksman, there was the brick’s slow-motion plummet as I witnessed the demolition of anything from old light bulbs and coke bottles to Matchbox cars and GI Joes.

Running out of things to destroy with our seemingly endless supply of bricks, we hatched yet another plan. Saving our allowance for the week, we bought gold spray paint across the street at Gibson’s Department Store and got to work. Our inexpert painting left nearby trees and bushes dappled and dripping, but I thought the bricks were pretty realistic, if a little on the large side. Sure that we’d worn out our welcome at the Dairy Queen, I decided to try the Exxon station. But old Mr. McCarley, the station’s owner, would be a harder sell than the toothy teen at the DQ. He was a former military sergeant with rolled up sleeves and tattoos, puffed chest, and a solid white flat-top. And his bark was just as bad as his bite, making him a perfect complement to old Ms. Queener. It was routine for Michael D. and I to hang around the gas station because it had the best vending machines. We’d hope to finger the coin returns and get lucky finding a previous customer’s forgotten change. Mr. McCarley would catch on and grumble, You kids stop playin’ ‘round those machines and git on home. Yes, sir. Yes, sir. But we’d be back.

Summoning courage from our recent success, we stumbled into the gas station and with practiced showmanship proclaimed (in unison):

“Mr. McCarley! Mr. McCarley! WE STRUCK GOLD!”

Old McCarley took one look at my drippy, over-sprayed brick and placed his thumbnail on its edge easily scraping the surface.

“This ain’t gold,” he said flatly. “It’s just an ole brick you done spray-painted.”

Michael D. and I flashed McCarley a look of mock horror, as if we were the ones who’d been duped. Then he shooed us out of the station and back to square one. Back to Tanglewood.

We should have known.