Chapter 2

The

Burial

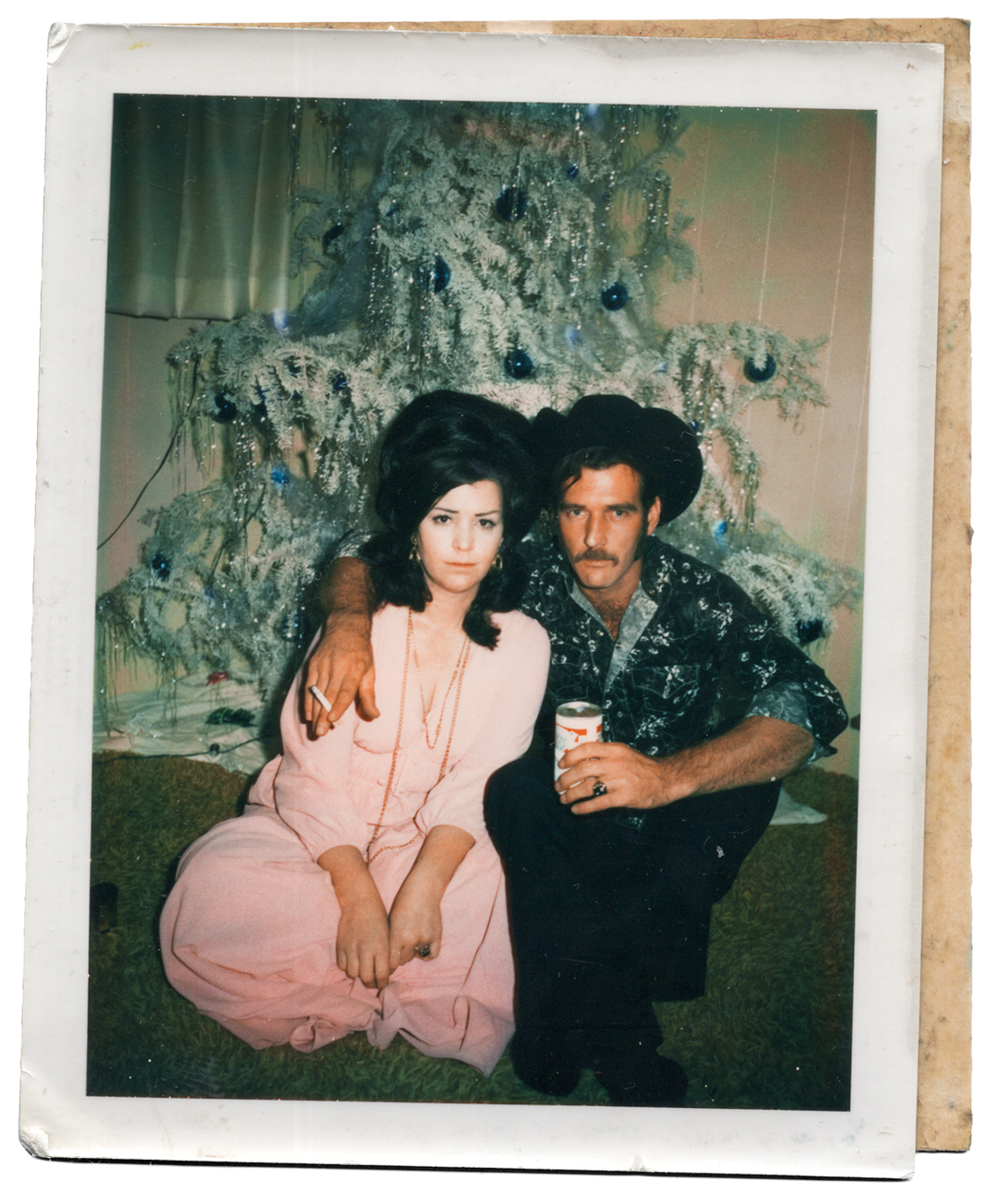

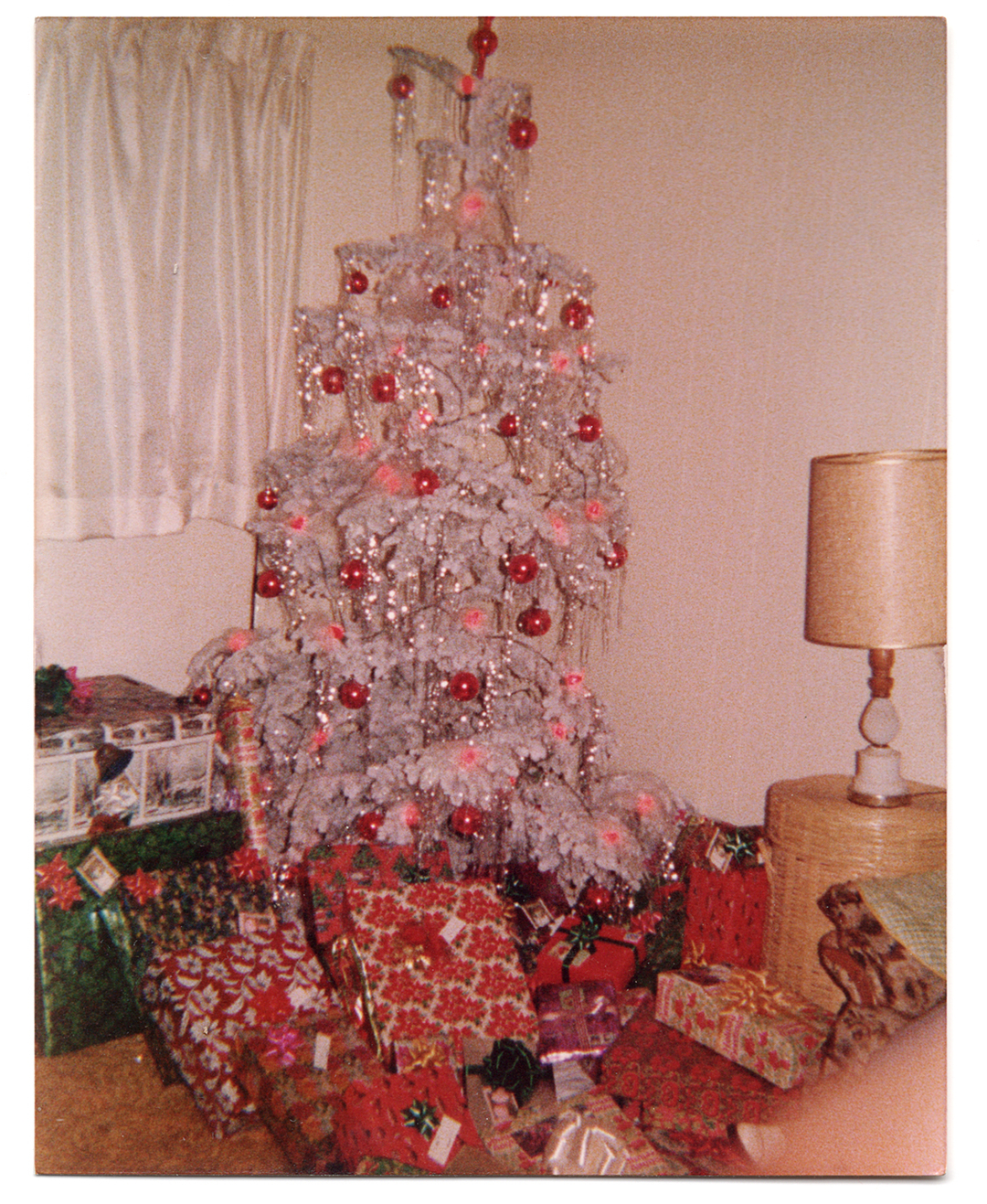

Photo: The one year Mom allowed us kids to decorate the tree. Kilgore, TX, Christmas, 1970.

Written by Michael Blankenburg

Published February 18, 2013

When I was five I wanted a purse for Christmas. That’s right. More than Matchbox cars, Lite Brite, or even the Uncle Wiggly board game, I wanted a red leather purse. It seemed a reasonable request at the time. The multitude of mysterious compartments inside, the pockets and clasps, fasteners and zippers, enthralled me. It was a warehouse of wonders—lipstick, compacts, hairbrushes, wallets, mini-notebooks, pocket mirrors (the little square kind with the brightly colored rubber case), toothpicks, bobby pins, safety pins, gum, TicTac, tissues, Tampax, cash, coins, and keys. All residing in the deep recesses of a woman’s purse. And I was often sent rummaging in my mother’s for one thing or another. MichaelWaaaaaaayne…? Find mama her purse and get me my . Whether it was cigarettes or hand lotion, laxatives or anxiety pills, I leapt at the opportunity to explore. I especially loved the efficient snap or zip when the mission—reconnaissance or otherwise—was accomplished.

But the request for a purse of my very own was met with raised eyebrows, a clearing of throats and suppressed chuckles. My brother rolled his eyes in the five-years-older-than-you-annoyed-sibling way. And mother gave her let’s-just-humor-him-during-this-awkward-phase smile. Nonetheless, I held onto the hope that Santa would come through despite my wanting a girl’s present. Maybe all those years at the North Pole with androgynous elves had taught him to see beyond gender.

Several weeks of exquisite anticipation were allayed thanks to the pursuit of our most expensive household purchase of the year—the Christmas tree. Appalled at those who wasted their money on cheesy artificial ones, we only sought out real trees which we’d then turn around and have flocked a snow white or one year, a pastel pink. This was mom’s way of saying that we were special, that we had class. And besides, all those fancy bank trees were flocked so why not ours?

What followed when the tree landed in apartment 16 was a gussying up that rivaled only mother’s daily beauty regimen. All red or all blue lights were coordinated with solid-colored, uniformly sized ornaments. Icicles were practically ironed then hung with great care strand by strand, making sure to balance the number and location according to the proportion of the tree. Mom’s special artist’s touch though was angel hair, the spider-webby fiberglass gauze that prickled your skin after only a few minutes of handling. She manipulated the angel hair at length to cover each bulb so they looked like spun glass nestled between the limbs. But the effect was more ghoulish than gay. Our tree looked like something from the Munsters rather than First National Bank. Nevertheless, after dark, with all the other lights off in the apartment, we basked in the fuzzy glow and thought it beautiful.

Christmas finally arrived. Nanda and Papaw were customarily buzzed. Mom’s boyfriend at the time, a tall skinny cowboy with mustache and opened western shirt revealing a hairy chest (Danny and I dubbed him Marlboro Man), tousled my hair giving me an unexplainable thrill. There were ooohs and aahhs when mom got her perfumes, bath salts and costume jewelry, and Oh Yeahs! when my brother saw his hot-rod model kit and Wilson NFL football. After all of the gifts but one were opened and wrapping was strewn across the floor, the room’s eyes turned to me and the large box of a present resting on my lap. Tearing through ribbons and packaging, tissue and tape, my hands sank down and seized the red leather purse with the golden square clasp. I held up the prize for all to see. Happy. Proud. But the excitement was short-lived. Smirks turned into raucous slow-motion laughter, distorted clown-like faces in a funhouse mirror. It was a joke. My face grew hot and I knew then that I was fundamentally, irrevocably different.

Bolting out of the apartment, I ran with the oh come here honey and it’s okays pelting my back. Only it was too late. I’d run to the end of the parking lot where the monolithic dumpster loomed before me and, straining to slide open its metal door, dug through the refuse of strangers and buried deep the object I had so coveted.