Chapter 12

Happy Got-Damned Thanksgivin’ Day

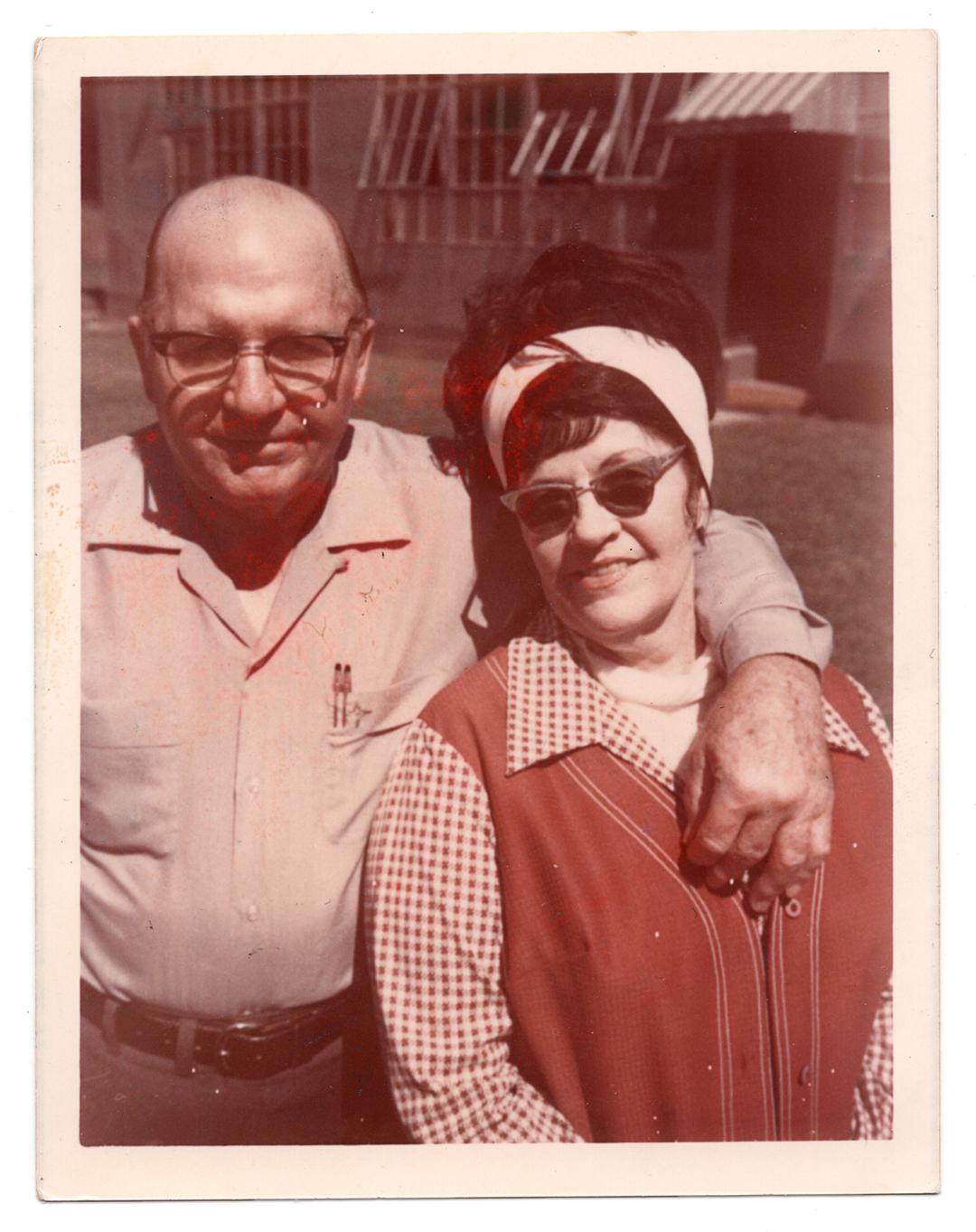

Photo: Pap in his all brown surroundings. 1978

Written by Michael Blankenburg

Published July 08, 2013

Thanksgiving and Christmas at my grandparents involved the traditional segregation of men in the living room watching football, the kids outside torturing some poor defenseless creature (horny toads and caterpillars or more likely, the youngest amongst our group), and the women scurrying about with pots of boiling water Pardon me, comin’ thoo! cooking and cleaning in the kitchen. Papaw would scrutinize their every move. Sum-un’s done burnt up sumpin’ in thar. Got-damn-it to hell! From his brown La-Z-Boy recliner—I hardly remember seeing him anywhere else—he sat in judgment, camouflaged next to the brown wood paneling that matched the wall-to-wall brown carpeting and all brown furniture. Even their Buick LeSebre was a shit brown with tan interior. And given the fact Nanda smoked at least a carton a week, I wondered if it was the twenty some-odd years of nicotine that had transformed a once moderately colorful home décor into the monochromatic suffocation I saw before me.

Papaw excelled in his role as cantakerous old man. In addition to his claims of someone burning up the kitchen just by turning on the stove, he was sure to critique anything from your sandwich-making to the opening of a box of cereal. Now why the got-damn hell you wanna go and do it that-a-way? Ain’t never seen nothin’ lak it in all mah lahf. He also kept a keen eye on the food inventory. He’d only buy things on sale and would hit as many stores as needed in search of an item’s lowest price. The jackpot was a sale on canned goods where he bought cases of blackeyed peas or hominy in preparation for the next Great Depression. Always suspicious of the grand total at the check out, it was Papaw taking the receipt from the cashier saying, Now wait a got-damned minute here…” Then one by one, he pulled out each item from the brown paper bag and checked it against his receipt, happily contesting any discrepancies. And there were always discrepancies. That ain’t what thuh newspaper said or Got-damn it I’ll show yuh thuh sign that was posted for them buhnanas right now!

In spite of his prickly disposition, Papaw did have a softer side. It came out when he told his stories. A couple of nips of vodka and he was loosed-lipped and ready to roll. With a scratchy and near unintelligible West Texas accent, he’d launch into such tales as his dropping out of the third grade to join a cattle drive or the one about borrowing $1.50 to marry “Mama” (Nanda) at the courthouse when she was just 15, he 17. And like any good showman, he often enjoyed a little prodding.

“Papaw, papaw, tell the one about the pet chicken.”

“Well, don’t rightly know ther’s much to tell,” his standard tease, smacking his lips (he refused to wear his dentures inside the house).

“Tell, it, Tell it!” we’d beg.

He leaned his head back in his chair and laced his gnarled fingers together, knuckles as big as walnuts. Papaw could barely shake hands and opted for a clumsy pat on the arm or a claw-handed swat on your shoulder. He warned that popping my knuckles would cause them to look like his one day. But I popped them anyway. I stared at his nose, hooked like a bird’s beak and all those tiny red blood vessels mapped across his face. His eyes, a milky pale blue and small, suddenly came to life. Then we sat in rapt attention as he began,

“Well, now, ya mama had gotten a baby chick fuh Easter ‘n she ‘bout 4–5 year ole. Named her “Helen.” An that damned little chick follerd her ever-whar, here ‘n yon. She couldn’ take one step aside the house wid-out Helen uh-follern her e’ry move. Well, now, that chick grewed into uh full grown chicken an was jus’ like uh got-damned puppy to Dell Rose. One night we heard uh ruckus out in the backyard an uh wild dog done gotta hold uh-Helen. Ripped her near tuh pieces. Dell Rose squalled and hollered, “Daddy save her, please save her!” Well, hell, I didn’t know what tuh do. So I got muh tackle box and uh needle and sewed that damned chicken back together with fishin’ line. Ole Helen did purty good for uh-while, but got-damn it if that sommabitch didn’t come back and finish thuh job. Poor Dell Rose damn-near ‘buhside herself. But I couldn’t save Helen this time.”

Beyond his hard-nosed exterior was a playfulness we didn’t get to see too often. As much as I feared Papaw, it was his storytelling that brought me closer to him, reminding me he’d lived other lives. I saw the glint in his eye as he told of the pranks and mischief he’d led in his youth. He’d rigged the outdoor clothesline so when the sheets were hung out to dry, they moved myseriously toward and away from the house; he’d devised a life-like hand from an inner tube painted with makeup to wave ominously from behind the window; and to scare fellow workers at the cotton gin, he’d built a dummy from a flour sack, gloves and shoes and put the dummy inside a cotton bale using mercurochrome for blood as if someone had been killed. So it was no surprise to find out he’d been the one to provide the thumping noises outside the house when Nanda had told me the Big Black Dog stories. Papaw grinning like a child. Papaw hiding in the bushes and banging against the side of the house. Papaw up to his old tricks.

After numerous spats among the women in the kitchen about who was doing what and how, after numerous accusations from Papaw that Y’all done toe up mah kitchen and still ain’t got nuthin’ to show fer it making an aunt or my mother start cry, the holiday dinner was served in the formal dining room otherwise off limits throughout the rest of the year. The room where furniture was normally covered in plastic and smelled of mothballs. The room that miraculously had colors other than brown, beige or tan. We held hands around the table with bowed heads and waited for Nanda to start the prayer. I always positioned myself next to her because I loved the way her hands felt in mine—the fleshy warmth of her palm, her ridged fingernails I rubbed with my thumb. Then in her Bea Arthur baritone the prayer would go something like this:

“Dear Heavenly Fah-thah, it is with great love and gratitude that we gather to buh-hold the bounty of your sacrifice… Dear Jesus, sweet Jesus, bless this day and each loved one here and those who couldn’t join us (may your spirit be with Jay and Sally as they vacation in beautiful Hawaii away from their loving family) and bless dear Hilma who’s left her husband for what she thinks are greener pastures, though Lord I’m not to judge, we leave that unto your gracious hands…”

As we followed the lilt and cadence of her voice, we’d anticipate the ending Amen and raise our heads only to hear another And dear Jesus… Back down they’d go. This would happen at least three or four times before anyone had the luxury of sitting down. Shortly thereafter a missing water glass, a misplaced table setting or a too-dry green bean casserole would send Papaw into a tirade. In his toothless drawl, Youspin’ awl got-damn day on this meal? Awl the got-damn trouble fur this big setup? And fur whut? It still ain’t right! along with the refrain, Never seen nuthin’ lah-kit in all, mah, lahf. Taking her cue, Nanda would start to cry and leave the room muttering obscenities. Papaw just gave a mocking smile to the rest of us who shifted uncomfortably in our seats. Well, now, Hap-py GOT-Damn Thanks-givin’ Day!

A few days after one of his conniptions, he’d apologize to Nanda by coming home with a carton of cigarettes or a double-meat What-a-Burger. She loved both with equal affection. See? she’d wink and give me a smile, Your grandfather’s a good man. Deep down he’s a really good man.

She didn’t have to tell me. I already knew.