Chapter 13

Ob-La-Di,

Ob-La-Da

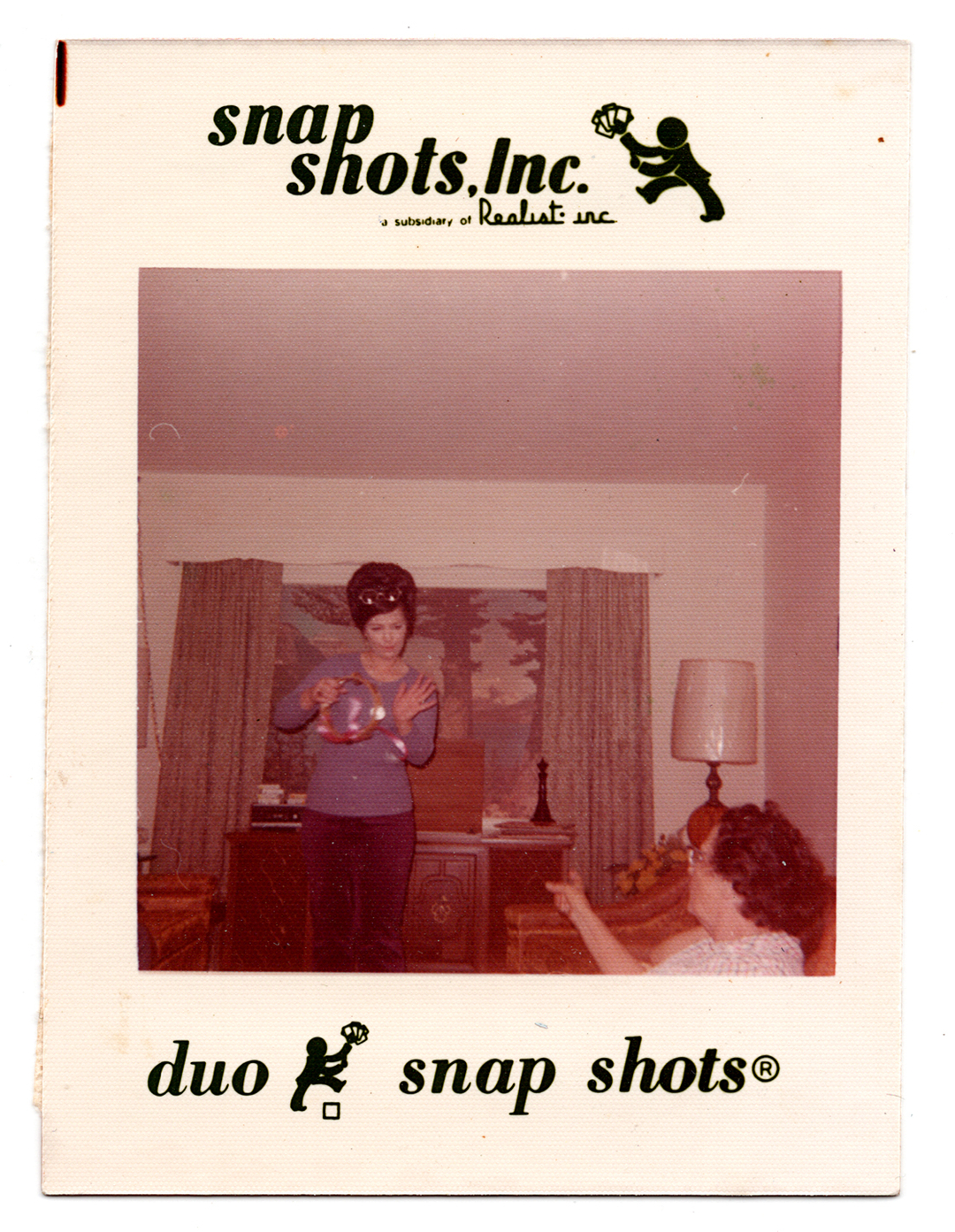

Photo: Mom entertaining, 1970.

Written by Michael Blankenburg

Published July 22, 2013

The slap and thrum of Mom’s guitar after midnight announced two things: she was entertaining guests (men, most likely) and that she had been drinking. A lot. While songs by John Denver, Joan Baez, Jim Croce and others made their appearance on her playlist, none got heavier rotation than the Beatles.

OB-LA-DI, OB-LA-DA… life goes on…

My brother and I would awake, groan loudly and cover our heads with our pillows. In the beginning, we found humor in Mom’s midnight revelries—there were giggles underneath those pillows instead of exasperated sighs. But repeat performances over the years wore down the novelty of it all and resentment seeped in. We stayed in our room, listening to the crest and trough of laughter, the hearty calls for “One more round!” or “Another song!” hoping it would soon end.

OB-LA-DI, OB-LA-DA…

Here we’d go again.

Dell Rose was a performer at heart. The guitar and tambourine her attendants on stage. But her guitar playing was spotty at best thanks to the Lee Press-On Nails and her voice, once trained on Baptist hymn standards, had taken on a rough-hewn Grace Slick quality, a result from years of heavy smoking. Often she’d run out of breath before the end of a phrase, straining to a tenuous whisper by the last word or two. The tambourine, on the other hand, never languished as she wind-milled her right arm, seamlessly tapping her hip in the downswing for wave after wave of shrill sound. Now and then she’d change up the pace with a 60s-esque dance move and alternating strikes of the tambourine on her hip and palm, her mouth open in concentrated effort to coordinate this fantastic show.

This show wasn’t always for her friends, though. After a few beers, she liked to perform for my brother’s or my friends as well. As her speech loosened, she’d try to impress them by peppering her sentences with slang like “Yo!” and “No Duh!” or some light profanity. They thought our mom was the coolest ever. We were mortified. As we got a little older and the occasional boyfriends and acquaintances had moved on, we were her captive audience. Sometimes it’d be whoever was unfortunate enough to be caught alone with Mom after she’d worked up a good buzz. Afterward, one commiserated with the other, brothers talking across a shared bedroom through the still darkness.

These late-night performances for Danny and me would sometimes take place in Mom’s bedroom, a Miller Lite and full ashtray at her side. Her very own private nightclub. She’d sit cross-legged in the middle of her bed in her pink nightgown while we stood awkwardly leaning into the foot of the mattress. But she always motioned us to sit on the bed and move in closer, closer. Songs were followed by stories of her band-playing days in Houston, how she’d worked two jobs to make ends meet and, finally, the life she could have had without us. Though we’d heard it a number times before, we still felt the sting of her regret. Knowing she’d crossed the line, she changed course and told us how much she loved us, how special we were, that having us was the best thing she’d ever done. A few more beers, another song and she laid the guitar flat on its back in her lap. Leaning forward and narrowing her black eyes, it began.

“Do you know how much I’ve done for you boys? Do you have any idea? Do you realize how I’ve sacrificed to put a roof over your head and food on the table?”

“Yes M’am we do,” we’d say. “We appreciate you mom,” we’d say.

Taking a long drag from her cigarette then talking through exhales of smoke,

“I just want you to have opportunities I didn’t. You boys can grow up to be anything you want. Any GOT-damn thing you want, unnerstand? Don’t let anybody tell you that you can’t do sumpthin’.”

The haze of smoke grew thicker, making it harder to breathe. Danny and I both feverishly sought for some way out, to be let go. But this was a dangerous game. One false move could fuel more of the erratic mood swings that shifted wildly from loving to spiteful, maudlin to malicious.

“I love both you boys so much, you know that? Do you know how much momma loves her boys? I’d do anything for you—Michael Wayne, get momma another beer, honey—and I mean anything. I’d give my life for you.”

Pronouncements of her undying love and selflessness would go on until one of us got fidgety or didn’t respond with just the right tone of respect and admiration.

“Well of course it’s never enough,” the bitterness creeping in. “You boys don’t know what sacrifice MEANS,” her volume increasing as she alternated inflections. “You BOYS don’t know SHIT about hard work and SACRIFICE!”

I was getting scared. Her mascara-smeared black eyes boring holes through us. Her big hair disheveled and tilting off to the side. Then it was a fight to hold back the tears.

“Oh Michael for God’s sake. Don’t be such a SISSY. You don’t even know what real sadness IS. Do you boys think your FATHER could have given you a better life than ME? DO YOU?”

“No, M’am,” we’d say.

“He’s never done ANYthing. Not one GOT-damn thing for you boys.”

Now, with her breath gusty and short, she tapped two fingers at the center of her chest until it turned bright red.

“But I’VE been here, I’VE been the one to pick up the PIECES.”

We’d sit stock still waiting for whatever came next.

“Alright then,” she recomposed herself and took another swill of beer. “Just one more, one more song. Let momma have one last song for her boys.” Then in a hushed, almost inaudible voice she’d sing us her favorite lullaby:

Where are you goin’ my little one, little one, Where are you goin’ my baby my own, Turn ‘round and you’re tiny, Turn ‘round and you’re grown, Turn ‘round and you’re a young man…

Here, she’d get choked up, pause momentarily, and through a strained and fragile breath…

Having babes of… your… own…

She’d look at us with tears in her eyes before strumming the final chord, then bow her head in dramatic conclusion paying heed to the emotionality of the moment. Danny and I sat in the uncomfortable silence. I hated this. We were expected to applaud, to be thankful, to appreciate, to love. All we wanted is to get away. Let it end. Breathe. She’d sense our discomfort and exhale through flared nostrils,

“Well,” pursing her lips, “Old Mom and her guitar playin’. Just being silly I guess,” a quick scratch to the back of her head, a tell-tale sign of her irritation. “Yeah, yeah. Well… go on to bed, boys, I suppose. It’s late. You don’t have to listen to ole mom anymore.”

“G’night, Mom,” we’d offer quietly, making a careful exit so as not to incite another encore—musical or otherwise.

OB-LA-DI, OB-LA-DA, life goes on, bra!

The percussive slap of her palm on the bridge of the guitar, her rings punctuating the contact. The loud strikes of the tambourine that rattled through the air. I grew to loathe these sounds. I knew the trap they set. The deliberate ostentation and forced showmanship. And the more she demanded, the less we wanted to give. Somehow we knew it’d never be enough.

It would be at least two decades before I could listen to any song by the Beatles. In the middle of a supermarket or a Sunday brunch with friends, a Beatles song would send me into a panic, looking for the exit. Only recently did I even realize what the song was about: Desmond and Molly’s love at first sight, their building a home sweet home with two kids running in the yard, and living happily ever after. And Molly’s still a singer in the band.

OB-LA-DI, OB-LA-DA… life goes on…